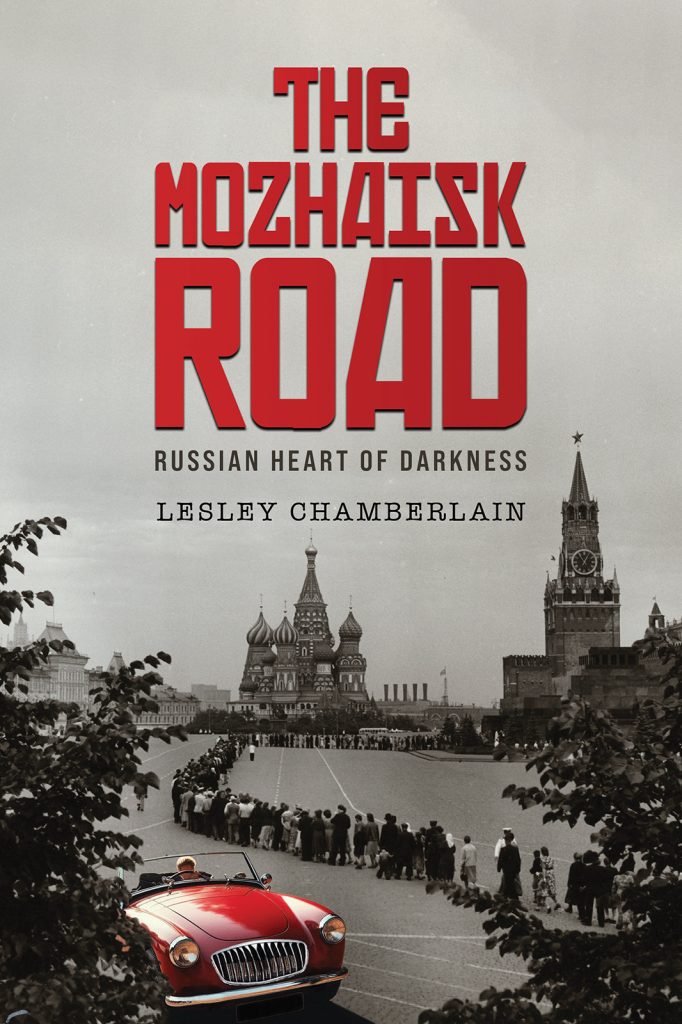

The Mozhaisk Road Russian Heart of Darkness

Russia is a country I’ve tried hard to understand. I’ve written about Russian food and Russian philosophy, Russian literature and Russian history. I’ve travelled the length of the river Volga to try to understand a mysterious and perplexing country. The Mozhaisk Road Russian Heart of Darkness is also the end of the road for me. It’s a novel that explores why Russia both attracts admirers across the world and is greatly feared. I fear it very much.

The year is 1979 and a rumour is going about Soviet Moscow that a second revolution is coming. As tired Communist banners still adorn the streets and Party newspapers carry mysterious, oblique commentaries cynics say it’s high time for change after sixty years of failure. For the city’s handful of dissidents who’ve been campaigning for change it’s a moment of cautious hope, as their old leader Alexander Razumovsky gives way to the younger Boris Marlinsky. But what has the Soviet leadership really in mind when one weekend Marlinsky disappears? Seen through the eyes of Gels Maybey, in flight from a cushioned life in the West, and journalist Howard Wilde (that’s him in the red car), reporting for London Global News, this novel takes the reader to the heart of who the nomklats are – the privileged top Party functionaries who, if the second revolution comes, have, out on the Mozhaisk Road, everything to lose. But then Gels and Howard may be losers too.

All the characters are fictional and, though I understand that Gels wanted to get away from money and Howard was just too in love with an alternative life to the West ever to leave, I have to say, as their creator, that I’m not sure about those Russians they keep watch over – whose secrets they try to understand. Not the good Razumovsky and Marlinsky but the wily Korsakov and his decadent entourage are the real stars of The Mozhaisk Road. How did they come into my mind? I’ll have a guess. I think they belong to what that great thinker Hannah Arendt once called, in a quite different context, ‘banal evil’. We’d never be like that ourselves. Or would we, if we were born into a system where we were powerless?

Or drop me a line if you’d like to buy a signed copy.

Don’t forget to leave a rating or even better a review wherever you buy it, and, of course, make The Mozhaisk Road Russian Heart of Darkness known on social media.

Rilke: The Last Inward Man

Rilke’s been on my mind since I first learnt German. It was Goethe, Hölderlin and Rilke taught me German was a beautiful language: musical, subtle and poignant. It’s all the little particles of meaning that matter, and a poet like Rilke (1875-1926) knows just how to juxtapose and vary those infinte shades of expression. Of course translating him into English is a task. But one thing I’ve tried to do in my latest book — brilliantly published by Pushkin Press — is to take away some of the unnecessary layers of complication that have accrued over the years. His linguistic picture-work is richly textured and imaginatively stunning, but also simple. Here he is, for instance, despairing at moments when inspiration — and the courage to lead his life at all — fail him:

Rilke’s been on my mind since I first learnt German. It was Goethe, Hölderlin and Rilke taught me German was a beautiful language: musical, subtle and poignant. It’s all the little particles of meaning that matter, and a poet like Rilke (1875-1926) knows just how to juxtapose and vary those infinte shades of expression. Of course translating him into English is a task. But one thing I’ve tried to do in my latest book — brilliantly published by Pushkin Press — is to take away some of the unnecessary layers of complication that have accrued over the years. His linguistic picture-work is richly textured and imaginatively stunning, but also simple. Here he is, for instance, despairing at moments when inspiration — and the courage to lead his life at all — fail him:

You take yourself from me, friendly hour.

Your wings flap and it hurts.

I’m alone: what’s the point of my mouth?

And my night? And my day?

I have no love, no house.

What do I stand on and where do I dwell?

All things to which I give myself

grow rich; I grow unwell.

My book is not a biography so much as a series of essays, or talks, starting with ‘How to Read Rilke Today’ and asking finally in what sense he is ‘The Last Inward Man’, lacking almost all desire to make his inner life politically and socially relevant. The two chapters on his years in Paris were a joy to write, while the section headed ‘Shall We Still Try to Believe in God’ helped me place Rilke as a modernist and not. (‘What will you do, God, when I die?’) He’ll always have a top place in the lineup of writers who have mattered to me over a lifetime, and, for the record, I also write about Rilke in connection with Heidegger in my book A Shoe Story (2014).

Nietzsche in Turin The End of the Future

The Last Inward Man is a companion volume to the Nietzsche in Turin I wrote a quarter of a century ago and first published in 1996. It’s great to have the Nietzsche reissued by Pushkin Press, so it can sit there on the shelf in the same design, different livery, as the Rilke.

The Last Inward Man is a companion volume to the Nietzsche in Turin I wrote a quarter of a century ago and first published in 1996. It’s great to have the Nietzsche reissued by Pushkin Press, so it can sit there on the shelf in the same design, different livery, as the Rilke.

There’s a marvellous final moment in Rilke’s poem ‘Archaic Torso of Apollo’ when he writes: you must change your life. The idea is that if the experience of a work of art is sufficiently intense that’s just what you’ll do. It strikes me as a pure Nietzschean sentiment and it reminds us just how powerful the art experience was to both writers. Art was a huge presence. It was also the shape of their own life, something they wrestled with, just as artists wrestle with their materials to produce order and coherence and beauty. There was this crossover between Nietzsche (1844-1900) and Rilke (1875-1926). It was the affinity between the philosopher writing in German who was also a poet, and the poet who for generations now has appealed to readers as a kind of philosopher. Some of Nietzsche’s last poems have an astonishing Rilkean ring. Some of Rilke’s sentiments, including that feeling of the loss of God, are close to what Nietzsche felt about the death of God, and how we need to invent ourselves anew. Both are masters of the German language. Just to recap on the gist of the Nietzsche book meanwhile: Nietzsche spent the last sane year of his life, 1888, as he struggled not to succumb to the symptoms of tertiary syphilis, in the stately Piedmont capital of Turin. There, and on his annual excursion to Sils Maria in Switzerland he wrote an astonishing six works, including his essay on Wagner and his autobiographical Ecce Homo. I write in the first line of this book that it was an effort to befriend Nietzsche, and so it was, for several reasons. One was that Nietzsche had a terrible reputation in the English-speaking countries after the 1939-1945 war. His ‘Superman’ — a misleading translation of the word Übermensch — seemed to make him a precursor of Nazi suprematism. That taint lasted a long time. While I was writing the book around 1993 I was introduced to a professor of English who turned his back on me when he learned of my work in progress. Another reason for the gesture of friendship on my part was simply that he was a writer who mattered to me — a spirit to whom I felt close.

Rainer Maria Rilke Duino Elegies, translated by Vita Sackville-West and Edward Sackville-West

I had only a small part in this volume but it completes the hat-trick of work of mine published in Spring 2022, so I have to mention it here. While I was working on The Last Inward Man I came across this translation of The Duino Elegies, which Rilke published in 1922. Parts of that great cycle of poems had been put into English, and quite a lot of Rilke’s other poetry was already available. But here was the first complete English version, originally published in 1931 in a deluxe edition by Leonard and Virginia Woolf’s Hogarth Press. Pushkin Press have unearthed it after so long. Readers used to a very modern-sounding Rilke rendered in free verse will meet something new in this blank-verse translation. The tone is loftier, the music more insistent. Edward Sackville-West, a novelist and composer who knew German well, and his cousin Vita, a prizewinning English poet in her day, moved the English reading of Rilke into a new gear with their landmark work — all of which I discuss in a short and I hope helpful introduction to this fringe-of-Bloomsbury enterprise.

I had only a small part in this volume but it completes the hat-trick of work of mine published in Spring 2022, so I have to mention it here. While I was working on The Last Inward Man I came across this translation of The Duino Elegies, which Rilke published in 1922. Parts of that great cycle of poems had been put into English, and quite a lot of Rilke’s other poetry was already available. But here was the first complete English version, originally published in 1931 in a deluxe edition by Leonard and Virginia Woolf’s Hogarth Press. Pushkin Press have unearthed it after so long. Readers used to a very modern-sounding Rilke rendered in free verse will meet something new in this blank-verse translation. The tone is loftier, the music more insistent. Edward Sackville-West, a novelist and composer who knew German well, and his cousin Vita, a prizewinning English poet in her day, moved the English reading of Rilke into a new gear with their landmark work — all of which I discuss in a short and I hope helpful introduction to this fringe-of-Bloomsbury enterprise.

Street Life and Morals German Philosophy in Hitler’s Lifetime

I somehow shared the shock of German writers and thinkers of a hundred years ago at what happened to Germany in the 1930s. Perhaps it was because in my early life I studied them as if Nazism never happened. The study of literature certainly wasn’t as politically and historically informed in those days. But perhaps it was also the case that I was drawn to something like art for art’s sake, and the equivalent in philosophy: philosophy for truth’s sake — though I have never heard anyone use the expression and I surely can’t get away with that use of the word ‘truth’ these days as if it were spoken by Plato.

I somehow shared the shock of German writers and thinkers of a hundred years ago at what happened to Germany in the 1930s. Perhaps it was because in my early life I studied them as if Nazism never happened. The study of literature certainly wasn’t as politically and historically informed in those days. But perhaps it was also the case that I was drawn to something like art for art’s sake, and the equivalent in philosophy: philosophy for truth’s sake — though I have never heard anyone use the expression and I surely can’t get away with that use of the word ‘truth’ these days as if it were spoken by Plato.

In any case in my book Street Life and Morals (Reaktion/Chicago University Press 2021) — whose publication has been masked by Covid – I retrace the birth and fortunes of certain themes in German philosophy as they arise in the late nineteenth century and what I want to know about is how the high-minded world of German thought is suddenly obliged to engage with astonishing social and political change. It’s a shock, almost a cultural revolution, and from the Kantian modernist Georg Simmel to the supreme literary modernist Walter Benjamin, philosophy struggles to come to terms with cities; that is with vast polities of strangers; and a street life full of intoxicating sensations; only in Benjamin does it strangely rejoice, and reset. What arises overall is a crisis for a country whose philosophical patron saint, in all but name, is the sober and inward-looking Immanuel Kant. Not inward-looking like Rilke perhaps, but inspired by religious tradition (Catholic in Rilke’s case, Lutheran Pietist in Kant’s).

The first half of my book is a survey of that street life as philosopher-novelist- journalist-critics like Siegfried Kracauer and the Mann brothers Thomas and Heinrich react to it. At the same time I show how the neo-Kantianism taught in the universities went through its own upheavals, with a remarkable switch from philosophy aimed at the perfect life, Platonically conceived, to the tribulations of ‘the bare life’, das bloβe Leben, the actual nerve-wracked, threatened physical life that most people lead. German philosophy makes this extraordinary switch from Idealism to materialism, with Marxism as an outlier in the pursuit of new human truths. Street Life and Morals asks where a more realistic socially-minded German philosophy can take its ethical standards, if it can no longer turn to Kantian inwardness (or the examination of private conscience).

The second half of my book looks in greater detail at how particular thinkers — Heidegger, Benjamin, Adorno, Horkheimer and the young Hannah Arendt (up to 1945) — work through their Kantian beginnings and take up new positions. I call them ‘rubble philosophers’ after the Trümmerfrauen who patiently cleaned the bricks to rebuild German cities after the second world war. I see these philosophers as dealing with a radical break in the history of humanist philosophy which occurred as much as thirty years before. Not everyone will be comfortable seeing Heidegger’s name on that list, but the context makes absolutely clear why his philosophy of Being-Here (Dasein) was a response to the vanishing plausibility of Idealism, and how Heidegger out-argued its last vestiges. It’s fascinating too to trace what links such diverse and conflicted figures as Heidegger, Adorno and Benjamin, despite the antipathy of the last two for Heidegger, and despite Arendt’s dislike of Adorno, love of Heidegger and protective fondness for Benjamin. In fact I mention Hitler very little. On the other hand the period in question — 1889 -1945, in case you had forgotten the lifespan of Hitler – shows just how the problems besetting the philosophers were the same problems besetting society and which eventually made the rise of Hitler possible. Those problems were a sudden disbelief in reason, a sense of how difficult it was for individuals — now commonly thrown together in urban crowds — to communicate one with another, and a mixture of cultural panic and excitement over the arrival of new technology. It is I think an extraordinary chapter in the history of philosophy and one thing I hope it does, in passing, is show that German philosophers were hardly supine in ‘allowing’ the rise of Hitler. They were engaging in direct social and political problems — but in their own terms.

Ministry of Darkness How Sergei Uvarov created conserative modern Russia

Readers of my work will know that I write about both Germany and Russia. These are the cultures I’ve studied most deeply and the languages I know best. I was a reader of Russian literature and philosophy before I ever gave a thought to Russian history and politics — but then who can read the great Russian novels and not feel caught up in the political destiny of mankind? German literature has traditionally been inward and linguistically complex, just like Rilke (though he was Austrian-born). By contrast, as I always felt it, Russian literature was social, which inevitably also means satirical. It remains full of urgent, often philosophical messages. ‘Formalism’ — what we might call art for art’s sake, though it was so much more — was officially outlawed in Soviet times. Well it’s a long story, with plenty of exceptions (the poetry of Mandelshtam, anything by Pasternak, and the essence of Pushkin, for instance). But it was the case that Russian literature, together with the country’s history and philosophy, made me sit up and take notice of the politics; and the man who crystallized those politics for me — way back in 1978, when I first encountered him — was Count Sergei Semyonovich Uvarov.

Readers of my work will know that I write about both Germany and Russia. These are the cultures I’ve studied most deeply and the languages I know best. I was a reader of Russian literature and philosophy before I ever gave a thought to Russian history and politics — but then who can read the great Russian novels and not feel caught up in the political destiny of mankind? German literature has traditionally been inward and linguistically complex, just like Rilke (though he was Austrian-born). By contrast, as I always felt it, Russian literature was social, which inevitably also means satirical. It remains full of urgent, often philosophical messages. ‘Formalism’ — what we might call art for art’s sake, though it was so much more — was officially outlawed in Soviet times. Well it’s a long story, with plenty of exceptions (the poetry of Mandelshtam, anything by Pasternak, and the essence of Pushkin, for instance). But it was the case that Russian literature, together with the country’s history and philosophy, made me sit up and take notice of the politics; and the man who crystallized those politics for me — way back in 1978, when I first encountered him — was Count Sergei Semyonovich Uvarov.

In fact it may have been a few years earlier, when I read a chapter by the emigre philosopher Alexander Koyré, in French, about Uvarov as the architect of Russian national policy in the 1830s, that I thought he was a man I should try to understand. He was the country’s Minister of Public Enlightenment, which was to say Education, from 1833-1848, but his brilliance carried his influence on tsar Nicholas I far beyond his official remit. Uvarov came up with the idea that the Russian ship of state needed to adhere to three tenets: Orthodoxy (or, let’s say, a common religion), Autocracy (which speaks for itself, still today) and Nationality, that is to say, Russian-ness. I usually translate that third term as Official Nationality, because though it was related to the Romantic idea of self-determination which had captured many hearts in nations across Europe at the time — think of Poland, Bohemia, Hungary — it was only ever tolerated in Russia as a set of feelings sanctioned and exploited by the existing power of the state. Russian narodnost’ was an emotional force and a source of potential social cohesion, but it was never going to be allowed as a revolutionary sentiment in tsarist times. But what a genius Uvarov was to distill this formula for the future of modern Russia! And what it explains to us about Russia still today! Here, in Orthodoxy, Autocracy and Nationality, was official conservative Russia’s answer to the quite different aims of the French Revolution: liberty, equality, fraternity.

I first worked on my biography of Uvarov when I lived in Moscow in 1978-79, and he helped me understand Soviet Russia like no other commentator. The terminology had changed, but the three great forces remained. They were now Marxist-Leninism, The Party and international Communist fraternity.

My book is not a wholesale condemnation of Uvarov, however, because I was fascinated by his personal plight, as a top Russian official. Whenever the Russian state presents an evil face to the world we’re bound to think of all those individual Russians who think quite differently, but dare not say. Uvarov’s fate was to be, as one historian put it long ago, the best-educated man of his generation and in a way a thoroughgoing European. Born in 1784 and partly educated in Germany, he was a classicist, an archeologist and a distinguished writer in French, with an entry in the Larousse Encyclopedia. His aim was slowly to introduce educational and hence social reforms to autocratic Russia, and in this he was quietly successful. Cynthia Whittaker in her book Sergei Uvarov The Origins of Russian Education spells out his remarkable achievement. But at what personal cost, I wanted to ask. Uvarov, often cast as the great reactionary in nineteenth-century Russian history, was in 1848, the year of renewed revolutions in Europe, dismissed from his post for not being reactionary enough. So Ministry of Darkness, published by Bloomsbury in 2019, is the story of one intelligent man’s agony at trying to serve conservative Russia because he found early in his life that anything overtly more liberal was doomed to failure. And even then he failed; or both succeeded and failed.

The Russian pursuit of Utopia

Russia sometimes seems all political machination and imperial and neo-imperial aggression, but then it has that quite different side to its culture: of great art and imagination, and fabulous political dreams. I’m glad I tried to do justice to that imaginative Russia before I took to spelling out so painfully the triumphant, repressive political conservatism of Uvarov. I keep both those Russias in my head, knowing I can’t reconcile them.

Russia sometimes seems all political machination and imperial and neo-imperial aggression, but then it has that quite different side to its culture: of great art and imagination, and fabulous political dreams. I’m glad I tried to do justice to that imaginative Russia before I took to spelling out so painfully the triumphant, repressive political conservatism of Uvarov. I keep both those Russias in my head, knowing I can’t reconcile them.

The book I devoted to Russian dreams was Arc of Utopia The Beautiful Story of the Russian Revolution and it was published in October 2017 by Reaktion. It had a fabulous cover, as shown above. But this gorgeous image was also in the running, It was an illustration for the Society of Wagnerian Art’s chamber performance of Das Rheingold in Leningrad in 1925 (in those twelve years after the October Revolution when the future of Soviet Russian culture was still in the balance, all modernist and Western influences not yet shut down). G. Kosyakov was the illustrator:

The Arc of Utopia was how I conceived the story of Russia that grew out of German Romantic philosophy. It created the idea of Russia as an ideal work-in-the-making, and as Russian artists and intellectuals transformed what they found in Goethe and Schiller, Kant and Hegel and Schelling, so they constructed a political blueprint on aesthetic lines. The ideal was one of togetherness and harmony: the beautiful life as a revolutionary politics,

I had wanted to write this passionate chapter in the history of ideas for years. (All my projects seem to have deep roots.) Arc of Utopia dated back to when I too — like those early nineteenth-century Russians — had immersed myself in German Idealism, in the hope of working out what was the good life to be lived. It was German Idealism — ultimately the philosophy of Hegel – that Richard Wagner set to music, some people say. Hence the pertinence of the image above.

I found myself in Soviet Russia even before I had finished with the Hegelian and Schellingist dreams of the Russian 1830s. Now it seemed I was confronted everywhere with a dream gone wrong — even while a Soviet newspaper like Pravda could still address the people as if it were speaking the Enlightenment message of Immanuel Kant.

The Soviet Russia of the 1970s, presided over by Party General Secretary Leonid Brezhnev, was a disaster with a secret poignant history. I wanted to tell the story of a dream of social transformation, inspired by philosophy but now driven into the ground. Of course it was a failure, but that’s not the only thing to understand about how Russia entered the modern world, especially, if, like me, you feel that Russia’s greatest asset is its creativity: its art, not its politics. Back in 1790 in Kant’s East Prussia, via the German Romantics in the 1810s and 1820s, and then from the 1830s amid their disciples in Moscow and St Petersburg, a certain aesthetic utopianism set the story in train. Kant talked about what he called our faculty of judgement. What made (and makes) us supremely human is to see the world not as it is but as it might be, as a beautiful and harmonious whole. I argue in Arc of Utopia that this vision carried forward by German Romanticism helped inspire the art, drama and politics that surrounded the anti-tsarist revolutions of 1905 and 1917. You can find a longer article about Arc of Utopia on my blog at https://lesleychamberlain.wordpress.com/2017/09/28/the-arc-of-utopia-in-the-anniversary-year-of-russia-1917/. www.reaktionbooks.co.uk on its Arc of Utopia page also features extracts from the reviews.

Debate

‘The Enlightenment’ comes under a great deal of attack but what does the term refer to? I worked on this theme in a stimulating three months at The Intsitute of Advanced Study at The University of Durham in 2014 and you can read the results in their online journal Insights 7 and also on my blog. The German Aufklärung is rather a different creature from its French and British counterparts, especially when it comes to the accommodation of religious and imaginative experience, so I give it special treatment. The extraordinary denigration of the Enlightenment by Adorno and Horkheimer needs to be understood in its historical context, and note taken of the authors’ own apologetic preface in 1972 to emotional views they expressed in exile in 1944.

Criticism

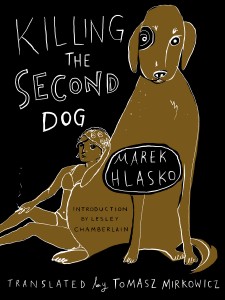

Marek Hlasko has been called the James Dean of Polish fiction in the 1950s but his filmstar good looks were nothing compared to ruthless stories he told based on his life as a truckdriver in a remote, snowbound part of the country, and on tough, depressing conditions in Poland post-war. From briefly being the darling of literary circles and the recipient of a state prize he became persona non grata and after an official trip abroad was refused reentry to his homeland. His life as an illegal drifter took him to Israel in the early 1960s, where Killing the Second Dog is set. He committed suicide in 1969. New Vessel Press has reprinted this short novel with my introduction, release date March 5th, 2014. Find out more!

Fiction

A short story, ‘Lighten our Darkness’, in Standpoint December 2013, and, meanwhile, not to forget, my novels

Anyone’s Game (Harbour Books, 2012)

Girl in a Garden (Atlantic, 2003)

and my short stories

In a Place Like That ( Harbour Books, 1998)

Work in the History of Ideas

Derrida features, along with Heidegger, as a key thinker in A Shoe Story Van Gogh The Philosophers and the West. In ‘The Sad Rider’, Common Knowledge Fall 2014 I draw out the good sides of his work generally. His name and reputation have been horribly traduced in Britain. Others still find him fascinatiing. My blog has never had so many hits as with ‘With Derrida in Oxford’ published in November 2014 .

Heidegger (1889-1976) was a philosopher working in a post-Darwinian age. I sketched some of the consequences of that historical position, and its consequences for Heidegger’s view of art, in an article for the TLS (26 Feb 2010). I’ve revisited the Heidegger-Darwin connection in the latest issue (Vol 88, July 2013) of Philosophy. Seen here up at the hut at  Todtnauberg, he’s become an inspiration for wilderness experience, amongst the many spillovers of his work from philosophy.

Todtnauberg, he’s become an inspiration for wilderness experience, amongst the many spillovers of his work from philosophy.

The Russian lingustician Roman Jakobson (1895-1982), who began life as a Moscow Futurist poet and ended it as an American academic has long been a puzzle to me. He was a key figure in the literary-intellectual aftermath of the Bolshevik Revolution, pursuing an internationalist modernism the new Kremlin ideologues, who were mostly traditionalists, not to mention ignoramuses, when it came to artistic taste, found unbearable. In exile in the interwar First Czechoslovak Republic he developed a science of phonology, or the importance of sound in language, which, together with his structuralist poetics, gave him a new way of examining literary works of art. The French structuralists of the next generation, preeminently Roland Barthes, overtook him when they applied structuralist analysis to all cultural artefacts, literary or otherwise, seeking to forge a new critical political tool. Literary critics also rebelled against Jakobson’s readings which seemed to them to take the pleasure out of reading. But others, particularly the novelist and critic David Lodge, have found Jakobson’s distinction between metaphor and metonymy useful in pointing to the distinctiveness of modern writing. Read my piece in The Times Literary Supplement September 20, 2013. What I want to add to the Jakobson story is the link between the intellectual-critical tools he forged and a traumatic life in exile, about which he was reluctant to talk. Jakobson’s personal reticence seems to dovetail with the observations of several critics that his theory uncannily echoes his life-experience and sometimes seems more autobiographical-creative than scientific. I believe this to be the case, and that it makes Jakobson all the more interesting as a now historical figure. I also talked about this at the Courtauld Institute’s London conference on Russian Exile Culture November 2-3, 2012. A version of what I said there can be found on my blog.

The Russian lingustician Roman Jakobson (1895-1982), who began life as a Moscow Futurist poet and ended it as an American academic has long been a puzzle to me. He was a key figure in the literary-intellectual aftermath of the Bolshevik Revolution, pursuing an internationalist modernism the new Kremlin ideologues, who were mostly traditionalists, not to mention ignoramuses, when it came to artistic taste, found unbearable. In exile in the interwar First Czechoslovak Republic he developed a science of phonology, or the importance of sound in language, which, together with his structuralist poetics, gave him a new way of examining literary works of art. The French structuralists of the next generation, preeminently Roland Barthes, overtook him when they applied structuralist analysis to all cultural artefacts, literary or otherwise, seeking to forge a new critical political tool. Literary critics also rebelled against Jakobson’s readings which seemed to them to take the pleasure out of reading. But others, particularly the novelist and critic David Lodge, have found Jakobson’s distinction between metaphor and metonymy useful in pointing to the distinctiveness of modern writing. Read my piece in The Times Literary Supplement September 20, 2013. What I want to add to the Jakobson story is the link between the intellectual-critical tools he forged and a traumatic life in exile, about which he was reluctant to talk. Jakobson’s personal reticence seems to dovetail with the observations of several critics that his theory uncannily echoes his life-experience and sometimes seems more autobiographical-creative than scientific. I believe this to be the case, and that it makes Jakobson all the more interesting as a now historical figure. I also talked about this at the Courtauld Institute’s London conference on Russian Exile Culture November 2-3, 2012. A version of what I said there can be found on my blog.